Breastfeeding Timeline

The First Weeks

Breastfeeding provides health benefits both to the parent and child, and can begin just moments after delivery for many. While it can offer a connection early on, can serve as the sole source of nourishment for an infant for the first months of its life, and fundamentally is natural, it is anything but easy for the vast majority of people.

If you choose to breastfeed (83% of people in the United States do!), being prepared, knowing what to anticipate, and understanding what’s within the parameters of normal can make all the difference. Knowing when there's an indication that you should seek help from a lactation consultant or healthcare professional ahead of time is critical.

With information on breastfeeding backed by research and validated by experts, we’re here to prepare you and help you every step of the way.

The First Moments After Birth: Prepare to witness human instinct at its most awesome — when held skin-to-skin at your chest, your newborn can actually make his or her own way to latch onto your nipple to feed, essentially by themselves. Research shows that early skin-to-skin contact after delivery benefits breastfeeding outcomes, cardio-respiratory stability, as well as decreases infant crying (by 10 times!). Hospitals designated as "baby-friendly" (indicating that they also serve as centers of breastfeeding support) and birthing centers routinely facilitate early skin-to-skin contact. This important step may be requested, or offered, regardless of your hospital's designation depending on its policies. It is a great idea to ask.

The First Days & Weeks After Birth: The body actually begins making breast milk during the second trimester of pregnancy. The earliest milk that comes in is called colostrum, which is a thick, yellow-hued fluid that’s earned the nickname “liquid gold” for its superfood composition of nutrients, protein and antibodies designed specifically for your newborn. If you’re concerned you’re not producing enough in your first days postpartum, don’t worry: Typical colostrum production is just 1-4 teaspoons per day, which is all it takes to prepare your baby’s tiny stomach (think marble-sized) for the next stage of breast milk.

Your baby may begin to cluster feed — or nurse in rapid succession, sometimes for hours at a time — before you’ve even left the hospital. While exhausting, the baby is actually cuing your body to produce more milk. Especially in the early days, breastfeeding is a supply-and-demand system: The more your baby nurses or the more you pump, the more milk your body produces.

Within two to four days after birth, your transitional milk — a combination of colostrum and breast milk — will come in. (Sometimes it can take up to five to seven days, especially if you’ve had a cesarean birth or high-intervention delivery.) The production is prompted by prolactin, the hormone responsible for milk production. Prolactin production is triggered by a variety of factors, including the delivery of the placenta (which blocked production of prolactin) and skin-to-skin contact.

A common challenge in the early days of nursing is sore nipples, which can develop quickly from issues with body positioning and latch (the way in which your baby attaches to your nipple). Getting assistance from a lactation consultant, a La Leche League or breastfeeding support group meeting, or someone highly experienced to help you understand what a good latch looks like is incredibly valuable, even if you feel like everything is going fine. Nipple soreness can also be the result of dryness, or insufficient skin elasticity. Moisturizing the nipples in the weeks leading up to delivery (and keeping up with it once breastfeeding) can help increase elasticity of the skin and prevent dryness and cracking.

Breast engorgement is a very common experience in the first week or two when transitional milk first comes in. Engorged breasts feel especially full or lumpy, with tight skin and are sometimes warm and painful to touch. Engorgement can be experienced throughout breastfeeding when milk isn’t getting extracted at its normal rate (like when you’re away from the baby and not able to pump or nurse, or even when there’s excessive stimulation from pumping). While there’s nothing you can do to prevent engorgement in the early days when transitional milk comes in, there are steps you can take to manage the pain.

Stage 1: 1-3 Months

The transitional milk you’ve been producing, which increases overnight as prolactin levels rise, turns to mature milk after about a month of breastfeeding. Mature milk has a higher fat content — think heavy cream vs. whole milk — which means the baby will fill up more quickly, ideally lessening the amount of time you have to nurse in each session. But even with shorter sessions, it may still feel during this period like you’re constantly breastfeeding. Don’t worry, it’s normal — and it’s finite. What’s important to understand at this stage is that the baby is hydrating with foremilk — or the initial milk your breasts produce each session — but satiated from the hindmilk, which contains a higher fat content.

To keep energy high, try to nourish your body with foods that are healthy and high in fiber — think leafy greens, nuts, oatmeal. There’s nothing you should stay away from when it comes to food (although high amounts of alcohol have been proven to inhibit your milk ejection reflex, leading to a dip in production). In fact, studies have linked eating a range of foods while breastfeeding with kids who are less picky when they transition to solid foods. If you’re struggling to produce milk, now is a great time to try foods and herbs considered to be good for production, like high-fiber foods and fenugreek (though check with your healthcare provider first if you have a thyroid condition — fenugreek can be a contraindication paired with thyroid medications).

Soft, stretchy bras that are designed for breast health (think: no underwires, no sports bras) reduce constriction that can increase the risk of clogged ducts and mastitis (painful breast ailments that are common reasons for ending breastfeeding sooner than intended), and are

comfortable on your healing and potentially sensitive body in the first months after birth. During these first few months of breastfeeding, soft and non-constrictive bras should be almost exclusively worn. This is why Bodily's bra selection is exclusively soft, stretchy, and designed with a lactation consultant.

If you’re returning to work at this time (25% of the U.S. population goes back within 14 days), this is the time to familiarize yourself with pumping if you haven’t already. It may be the first time you physically see the amount of milk you’re producing. (Fun fact: Breasts on average produce 3-5 ounces total at one time. This is an average, which means some people produce less and some produce more. None of it is wrong.) It also means connecting with your HR or direct manager to understand how your workplace accommodates breastfeeding employees. If you’re planning to introduce formula, supplement or wean completely, plan ahead so you (and your baby) can adjust before your return, and ensure you have the appropriate supply of breast milk or formula on hand.

Stage 2: 3-6 Months

For many new parents, a fog seems to lift around month three. A lot of that has to do with your baby’s development, but it’s also tied to milestones reached in your birth recovery and breastfeeding. Nursing is often more relaxing in this stage, as parent and baby have figured out what works for them.

If you’re still exclusively or mostly breastfeeding, production levels have balanced out, but nursing or pumping every two to four hours (or as often as the baby feeds) is still necessary to maintain supply and avoid clogged ducts. During your baby’s growth spurts, it may feel like you’re back at the beginning — frequent nursing sessions and cluster feeds can leave you exhausted. Don’t worry, they’re temporary.

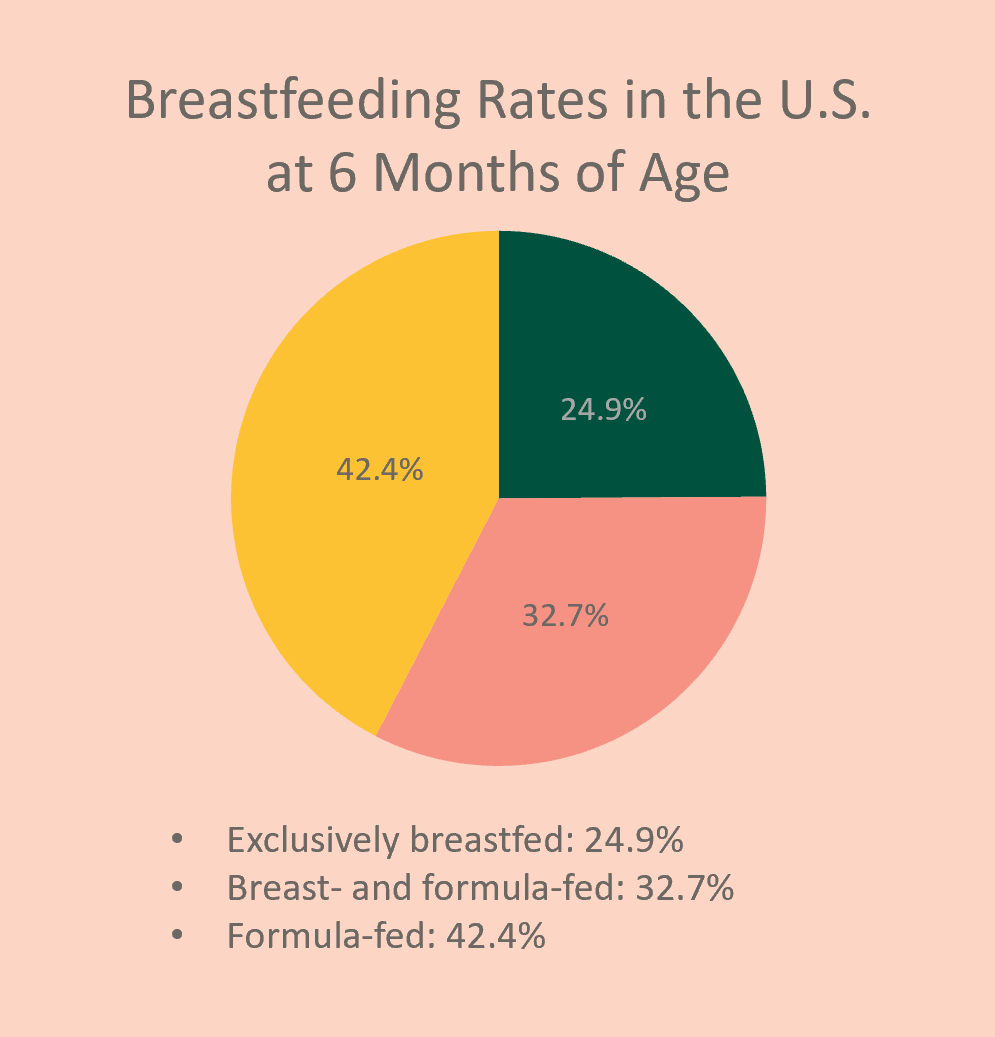

Only a quarter of babies exclusively breastfeed by six months postpartum. Most parents decide to formula-feed, or opt for a combination of the two: Supplementing breast milk with formula is a good option for those who want to continue to breastfeed but, for whatever reason — a busy work schedule, a struggle to produce, a prerogative — want to support feeding with formula.

Stage 3: 6 Months and Beyond

Many babies are introduced to solid foods around now, which may result in you nursing less, though their nutrition will still come from breast milk. If there’s a dip in production and you are concerned about not having enough milk — which can be a surprise during a stage that otherwise feels really comfortable — consider leading meals with a nursing session to ensure your baby empties your breast before eating solids.

Another dip may happen in this stage — this time tied to the return of your period. Not only do you have the chance of getting pregnant as your cycle returns (and that can happen even before your first postpartum period: on average, the first postpartum ovulation happens 45 days after birth), but your production can wane as well as your hormones fluctuate. Don’t panic: The drop in supply is temporary.

A lot of things about breastfeeding get exponentially easier over time, but one thing makes it harder: the size of your baby. Parents can develop shoulder and back pain in general when breastfeeding, but especially as the weight they’re supporting gets heavier — so now’s a good time to revisit positioning.

Anything goes when it comes to nursing bras at this stage. If you want to wear an underwire, a molded cup — whatever you preferred before childbirth — consider yourself in the clear.

Weaning

Whether you’re weaning at three months (or earlier) or two years (or later), a slower process is always ideal. Dropping a single feed every week or two is a recommended pace, both physically and emotionally — for you and baby. If you wean too suddenly, there’s physical discomfort that can develop due to engorgement.

Emotionally, there are hormonal fluctuations — like a drop in prolactin and oxytocin, which are higher in lactating women, along with shifting estrogen levels — that can feel overwhelming on top of the emotions you may already be feeling from ending the journey. While there isn’t a lot of research on the topic, post-weaning depression is a real thing, and it deserves the same care and attention that postpartum depression does.

While it’s commonly thought that breastfeeding can affect breast size and shape, , those changes are more likely attributed to factors like weight gain and number of pregnancies. Breastfeeding doesn’t have an adverse effect on breast shape or size — your breasts should return to pre-pregnancy size around six months after you’ve stopped, once the fatty tissue has replaced milk-producing tissue.

Take it slow. However long you chose to breastfeed (if you chose to breastfeed), feel proud you made it as long as you did.

-v1729531950562.jpg?830x1020)